Preparing students for the mathematics exam

Past, practice and specimen papers are done by all of us. It is a tried and tested means of getting students used to question style, wording, topic mixture and many other aspects of the exam. Sometimes I feel that we can give students past paper exhaustion – that they are ‘past-papered-out’ by the time the actual exam comes around.

This year we tried to look at how we could use some of last year’s papers in a more structured and reflective way. In April we decide to use one of them as a mock exam (and as a reality check) but to analyse the results in a different way.

I am an active Twitter user (@cpstobart on education related topics only) and there are a number of inspirational maths leaders and teachers out there. Via weekly Twitter conversations at #mathscpdchat and #mathschat, which I join in when I can constructively contribute, ideas are suggested and developed.

I was particularly interested in one idea which required recording the mark gained for every part question for every student. Putting these into a spreadsheet which is colour coded for the marks gained, presented an amazing map of accuracy and understanding.

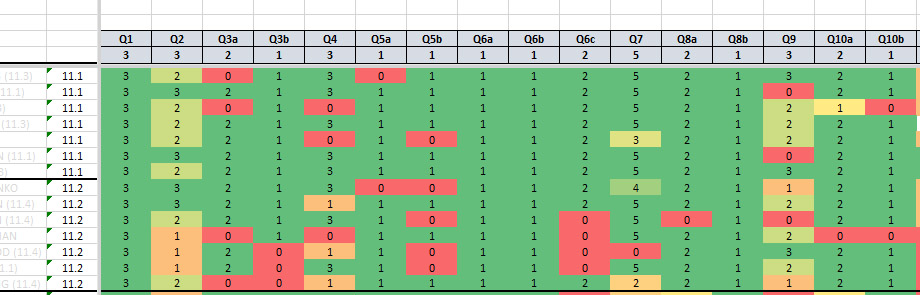

Here is a portion of the ‘map’:

The header rows tell you the Question number and the marks available. Each following row is the set of marks gained by each student, and each column a part question. Colours range from green (full marks) to red (no marks).

The question for us is, What can we do with this information?

We can identify which questions were done well by virtually all students (topics do not need revision) and some which were done poorly by many students (intervention required). We could also see where students had started a question successfully but then did not manage to follow through to a second or third part – why not?

Initially we had thought that we could rearrange students into new groups where students that had the same problem topic could come together for a couple of lessons, then rearrange again, and again. This would provide better managed and targeted revision.

Although this would have been a very good exercise what we discovered was that there were a few part questions where everyone performed poorly. This meant we could keep the classes as normal and tackle the same problem in every group.

The difficulties arose from interpreting and decoding questions successfully. On closer inspection we discovered questions where particular wording had been the problem.

This could have been an unusual context that the question was set in, specific mathematical vocabulary that is muddled, or a cultural misunderstanding. It was surprising how widespread some of the problems turned out to be – but we would not have been able to identify them without this expansive overview.

In many instances, once vocabulary issues were rectified solutions were then successfully found without any further help needed. This does highlight, for us, the importance of vocabulary and context. While we do make extensive use of student word banks we can never relax our efforts to ensure that they are regularly updated. For many students, just a small amount of help resulted in big rewards because a question was suddenly unlocked.

Was this a useful exercise? Without doubt. We had a preconceived idea about what we were going to do but the data took us in another direction along a route that was, ultimately, better than our original idea.

Would we do this again? Absolutely. Having the overall map of student achievement by part question is a terrific snapshot of their levels of understanding. It offers suggestions about the type of intervention that can be usefully employed to clear up misconceptions and deepen understanding.