February 24, 2019 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

It does not matter how we describe it: mathematics learning difficulties; digit dyslexia; arithmetic learning disabilities… there is a phenomenon affecting an estimated 5% of the population. They have difficulty learning and remembering arithmetic facts. They have problems solving problems that involve calculation. The problem these people encounter with numbers is often masked by another difficulty – for example dyslexia.

Dr Josef Gerstmann first started to investigate and write about the difficulties experienced in learning or comprehending mathematics during the 1940s and the term dyscalculia, meaning ‘counting badly’, was coined about 1949. However, it wasn’t until the mid 1970s that, through the work of Ladislav Kosc, dyscalculia was defined as ‘a structural disorder of mathematical abilities.’

What is dyscalculia? Well, there is a wealth of information out there explaining what it is (and isn’t). Good places to start might be the British Dyslexia Association whose website has a section for dyscalculia – it is widely acknowledged that many dyslexics do have dyscalculia. It is worth noting that there is no causal connection between these two. There is, however, a strong connection between students displaying dyscalculia and (maths) anxiety – this should not come as a surprise. Look also at dyscalculia specific organisations such as DyslexiaScotland.org.uk or the Dyscalculia Information Centre.

As a mathematics teacher I need to recognise that I will come across my share of dyscalculics. Just because a student seems distant, anxious or even lazy, has poor attention, or just generally bad a maths, does not mean that they are dyscalculics – but these traits might mask dyscalculia, some of them may be learned ways that the student copes with their difficulty. It means of course that I have to be very sensitive to these students’ needs and to quietly investigate their computational and processing skills.

Dyscalculia cannot be cured, you do not grow out of it. But, it can be managed, skill sets can be improved, strategies can be learned, attention and working memory can be developed, anxiety can be relieved. It is my job to ensure that students are given back their sense of number, to correct a poor concept of number, to start to acquire in a concrete way those foundation blocks that all other concepts are built upon.

This is not, cannot be, a quick fix. Intervention is not about helping out with homework or repeating lessons on a 1 to 1 basis with a student. It is about identifying the mathematical connections that the student does not have, working to build factual blocks that will allow more cumulative skills to be learned. It could be slow – it will depend when intervention starts.

As I build my awareness of this learning difficulty, my experience of working in 1 to 1 relationship with dyscalculics, and evaluate the success of my intervention, I aim to post occasional updates on my reflections and discoveries.

June 29, 2018 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

Past, practice and specimen papers are done by all of us. It is a tried and tested means of getting students used to question style, wording, topic mixture and many other aspects of the exam. Sometimes I feel that we can give students past paper exhaustion – that they are ‘past-papered-out’ by the time the actual exam comes around.

This year we tried to look at how we could use some of last year’s papers in a more structured and reflective way. In April we decide to use one of them as a mock exam (and as a reality check) but to analyse the results in a different way.

I am an active Twitter user (@cpstobart on education related topics only) and there are a number of inspirational maths leaders and teachers out there. Via weekly Twitter conversations at #mathscpdchat and #mathschat, which I join in when I can constructively contribute, ideas are suggested and developed.

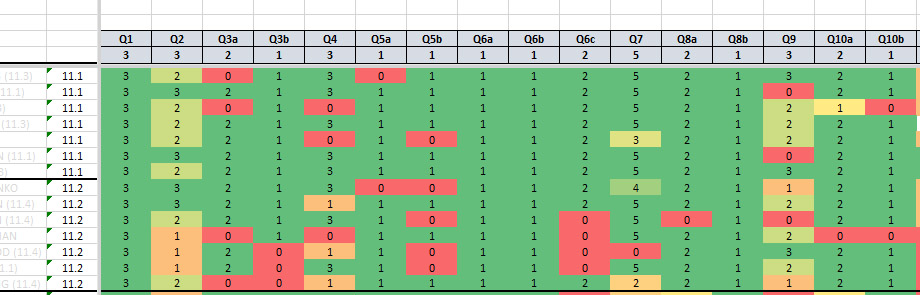

I was particularly interested in one idea which required recording the mark gained for every part question for every student. Putting these into a spreadsheet which is colour coded for the marks gained, presented an amazing map of accuracy and understanding.

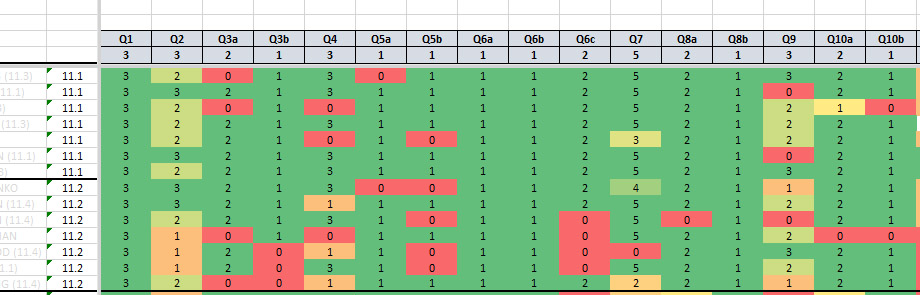

Here is a portion of the ‘map’:

The header rows tell you the Question number and the marks available. Each following row is the set of marks gained by each student, and each column a part question. Colours range from green (full marks) to red (no marks).

The question for us is, What can we do with this information?

We can identify which questions were done well by virtually all students (topics do not need revision) and some which were done poorly by many students (intervention required). We could also see where students had started a question successfully but then did not manage to follow through to a second or third part – why not?

Initially we had thought that we could rearrange students into new groups where students that had the same problem topic could come together for a couple of lessons, then rearrange again, and again. This would provide better managed and targeted revision.

Although this would have been a very good exercise what we discovered was that there were a few part questions where everyone performed poorly. This meant we could keep the classes as normal and tackle the same problem in every group.

The difficulties arose from interpreting and decoding questions successfully. On closer inspection we discovered questions where particular wording had been the problem.

This could have been an unusual context that the question was set in, specific mathematical vocabulary that is muddled, or a cultural misunderstanding. It was surprising how widespread some of the problems turned out to be – but we would not have been able to identify them without this expansive overview.

In many instances, once vocabulary issues were rectified solutions were then successfully found without any further help needed. This does highlight, for us, the importance of vocabulary and context. While we do make extensive use of student word banks we can never relax our efforts to ensure that they are regularly updated. For many students, just a small amount of help resulted in big rewards because a question was suddenly unlocked.

Was this a useful exercise? Without doubt. We had a preconceived idea about what we were going to do but the data took us in another direction along a route that was, ultimately, better than our original idea.

Would we do this again? Absolutely. Having the overall map of student achievement by part question is a terrific snapshot of their levels of understanding. It offers suggestions about the type of intervention that can be usefully employed to clear up misconceptions and deepen understanding.

December 10, 2016 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

In the UKEdMag of October 2016 Kara Collins (@karadubai28) wrote a short and thoughtful article titled: ‘I’m rubbish at Maths’ How personal experience can influence teaching.

In the UKEdMag of October 2016 Kara Collins (@karadubai28) wrote a short and thoughtful article titled: ‘I’m rubbish at Maths’ How personal experience can influence teaching.

This is very honest reflection of early experience when faced with a maths challenge. Is this a kind of maths ‘anxiety’ or phobia? Where does it come from? How does it become such a difficulty?

An AHT once said to me, when discussing a colleague, ‘There are people who teach maths and there are mathematicians.’ The person we were talking about was indeed a mathematician of the highest calibre, but it also made me reflect on my own experience. I am a definitely a ‘maths teacher’ and not a mathematician, but I have a love for maths and the challenges that finding solutions present.

‘I’m rubbish at maths,’ is commonly heard in secondary schools. I say schools rather than classrooms because teachers are guilty of uttering this phrase as well. However, the same can be heard at home as well. As Babtie and Emerson report in their book ‘Understanding Dyscalcula…’ (2015, pg 55-56):

In many western countries there is a tacit anti-maths view. Failure in mathematics is deemed acceptable in adulthood. Parents, and some teachers, will make remarks such as: ‘I was always bad at maths.’ ‘This is really hard.’ The remark is often accompanied by a laugh. Often this is in the context of basic numeracy in the first few years of school. As a result children may receive confusing signals. The subliminal message is that maths is so hard even mum and dad find it difficult, and maths doesn’t really matter.

And this is the difficulty we, as teachers of maths, encounter.

Maths anxiety is defined as a feeling of tension and worry that interferes with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in everyday situations – not just in the classroom. It’s a debilitating emotional reaction to solving problems involving numeracy.

There is not a single, or isolated, setting where this originates. As suggested above, a student’s family and educational situation can contribute, and when additional factors (such as poverty, access to education – particularly at a young age) surrounding these are considered, it is no wonder that we are not only presented with students who struggle with basic mathematical concepts and processes, but also ones that are turned off maths. The off-switch may well have been flicked by no other reason than the weight of an opinion by a peer, parent, significant other…

The old wives’ tale, or a much-retweeted factoid, that if you say (or hear) something often enough you will start to believe it applies here. What’s known as the Illusory Truth Effect is the idea that if you repeat something often enough, people will slowly start to believe it’s true. And the effect is much stronger than we imagine. The steady drip, drip, drip that maths is difficult, doesn’t matter… will eventually convince perfectly capable student that this is, in fact the case.

How do we combat this? A number of times I have tweeted about culture in the classroom, about the positives of peer-to-peer work, of in-class marking and feedback, of the need to constantly build numeracy confidence.

Confidence boosting is a vital and sometimes missing ingredient in many maths classrooms. As HoD I always elect to be timetabled with the lower ability groups because one of my prime concerns is the stream of students who will walk into the department that first week in September and say, ‘I’m rubbish at maths.’ Sometimes it is interesting to explore where this mindset has come from, but from the first minute in the classroom the primary objective is to reverse it.

We attempt to measure progress in a variety of ways. End of term reports sometimes end up being lists of achievement, and this has its place, but other mentions about attitudinal or emotional challenges met and mastered are equally important.

For me the autumn term is more about whether students end up at Christmas with a changed attitude, a raised level of confidence and the realisation that maths isn’t hard, that it does matter and they needn’t by anxious about walking through my door. Put these things in a report and, together with the change of heart about maths visible in their children, maybe parents will also start to realise that maths isn’t hard.

November 1, 2016 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

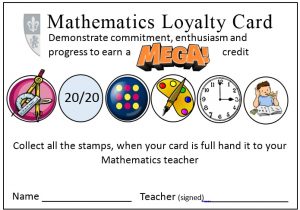

Having picked up this idea many months ago, finally launched our version of the Maths Loyalty Card with Y9.

Having picked up this idea many months ago, finally launched our version of the Maths Loyalty Card with Y9.

We identified 6 areas of student activity that we wanted to reward such as demonstrating improved understanding, contributing to displays, performing well in tests, bringing correct equipment to lesson… For us the reward is linked to the school ‘credit’ system, offering a MEGA (read multiple!) credit, but you could just as well offer bars of chocolate, some free drinks/cakes from the dining room….

We anticipate that a student will take the best part of a month, especially when testing is involved, to complete – but let’s see!

Here’s the loyalty card in .docx format.

Many thanks to TryThisTeaching for the original idea.

October 29, 2016 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

Creating the schemes of work for the new 9-1 syllabus has not been an easy task. We had, of course, mapped out the whole two years for the start of last year when the then Y10 we starting, but we didn’t know how things would map out.

I think we did a pretty good job with students as Y10 and we haven’t needed to tweak the Y10 scheme very much from 2015/16 to 2016/17. We did find that we could play a little bit with the original version of the Y11 plan. When we came to the end of June we found that we had actually done more than we had planned. This meant that we could build in a few revision weeks.

We also do the GCSE in 1 year. Squeezing everything into 25 or so weeks is pretty tough. The only way we can be sure of managing this is to employ the strategy of flipped lessons and independent learning. We have to assume a great deal of prior learning has happened somewhere in our students’ lives and build study sessions and homework around that assumption. We chose to really pile this into term 1 so that we have breathing space starting in January – where our mock exams also kick in.

So far, after the first half term things are going reasonably well to plan. Inevitably it is the sets where we have weaker students that a little ground has been lost, but with that study/ homework time freed up next term we can claw some of that.

Our schemes of work are here in .pdf

Y10 scheme

Y11 scheme

GCSE maths in one year

If this helps you to look at how to pack things in, great.

Happy planning.

Colin

July 20, 2015 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

Having just completed (apart from the tidying up, query and edit process) the authoring of a collection of materials to accompany the new Collins 4th edition Mathematics GCSE Foundation student book, it is apparent that AO3 has really become a focus of the new changes.

Having just completed (apart from the tidying up, query and edit process) the authoring of a collection of materials to accompany the new Collins 4th edition Mathematics GCSE Foundation student book, it is apparent that AO3 has really become a focus of the new changes.

The brief required, for each chapter of the student book, a context based problem that “will help to build students skills and confidence for tackling (AO3) problem-solving questions.” When these are made-up into a video there will be a worked solution with audio commentary that talks the students through a suitable strategy for tackling the question and the skills needed to solve it.

There was a need to offer an evaluation opportunity, so that students could be prompted to evaluate the method used and the answer obtained. There also needed to be an opportunity to consider whether alternative methods could have been used.

The difficult task was not in creating contexts in which to locate problems, but thinking of ways in which to incorporate the syllabus requirements embedded in AO3, that students should be able to:

- interpret results in the context of the given problem

- evaluate methods used and results obtained

- evaluate solutions to identify how they may have been affected by assumptions made.

These will, within questions at Foundation Tier, make life difficult for students.

In the past, a question looking at different methods for purchasing something – a deposit of varying percentages followed by differing monthly payments – would require an evaluation of the results, but not the method used. Previously students have encountered questions that ask them to explain, show, prove but not to also incorporate comments about assumptions that they have made, or indeed a comment about the method they have used.

On top of this, more questions are going to be set in a context from which students will be required to extract information rather than be presented with a rather stark equation to solve or diagram asking them to workout x. So not only is there a requirement to interpret results, they have to interpret the question accurately as well.

This is going to present huge challenges if, like me, you work with students whose first language is not English, or students who maybe have poor literacy skills.

So what kind of questions can be expected, and how are they to be answered.

For example, when looking at properties of number I had a scenario involving three looping tracks in a model railway, circuit times were 18, 20 and 28 seconds. Part of the question involved finding the highest common factors of these numbers (1260 seconds or 21 minutes). The most efficient method is to use prime factor form (arrived at by different methods) but students could have started producing strings of multiples – an agonisingly long process, 18 would have a list of 70 multiples before arriving at 1260. For this part of the question an evaluation of method is possible, comparing the use of prime factors with the use of lists of multiples.

When examining direct proportion we are all used to questions such as, 3 men take 6 days to build a wall. How many days would it take 4 men to build the same wall? We would expect most of our students to come up with an answer of 4½ days, but would we also expect them to add that they assumed that the length of the working day was the same in each case, or that the 4 men worked at the same rate as the 3 men?

Questions may contain phrases such as, Show how this is possible. This is the clue to an evaluative solution being required. Not only do students need to produce a numerical answer, they then have to comment on that result, such as making a comparison of the result against an alternative. The question could also be one of comparing a method, for example, simple percentage change against repeated percentage change.

Because of context setting it is clear that students will have fewer clues as to the solution from the question itself – simple percentage change and repeated percentage change solutions might be triggered in a student’s mind by key words such as bank account, percentage interest, number of years invested. For example, I used the declining numbers in a wildlife population to cover this topic and, after calculating a population in a given year, ask students to evaluate models that two bird watchers had used to arrive at a forecast of population numbers. Students need to carefully consider the nature of the problem, devise a strategy, communicate the developing solution, and provide an evaluation with summary conclusion. The wording of questions will not immediately signal the method of solution.

We might conclude that from now on there is a good deal more narration expected.

Communicating method, describing the steps taken, clearly explaining the significance of a solution; these are the skills being extended under the new syllabus and embedded in assessment objective AO3.

June 5, 2015 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

The Twitter storm that erupted last evening was amazing. Thanks to Hannah and her sweets, plus 180,000 (and counting) tweets to #EdexcelMaths, the grim details of the examination has reached into the homes of every listener of the Chris Evans Radio 2 Breakfast Show, and all BBC/ITV news watchers. I was on Twitter last evening and post were coming in faster than you could scroll down the page.

The Twitter storm that erupted last evening was amazing. Thanks to Hannah and her sweets, plus 180,000 (and counting) tweets to #EdexcelMaths, the grim details of the examination has reached into the homes of every listener of the Chris Evans Radio 2 Breakfast Show, and all BBC/ITV news watchers. I was on Twitter last evening and post were coming in faster than you could scroll down the page.

So what was being said? 99% of tweets were from disgruntled students who were expressing their anger and grief in ways both funny and vitriolic. By this morning the tide was turning with a healthy percentage of tweets asking what all the fuss was about. The paper is written to cater for students of middling ability up to those gifted students eager to move on to study at A level, and so is it not to be expected that there will be some students that find some of the questions on the paper more challenging or even no-go areas?

I had a read through the examination paper at the time and was pleased with the range of question topics, their setting/context and their degree of difficulty. I did not turn the page and stare in disbelief at a question that looked like it had migrated from an A2 paper. Yes, there were some tricky questions, and yes there were some pleasing twists to the expected questions, but none that deserve the furore that has mushroomed over that past 24 hours.

One tweet I did read challenged the methods by which students are taught. This is a good point. There is often a strong emphasis on doing mountains of past papers and learning the mark scheme – in other words preparing students for a particular style of question and learning how to answer in a particular way using particular key word/phrases. Of course, working through past papers is an invaluable exercise – we need to let students see the style of the papers, get a feel for the way in which questions are asked and see why marks are allocated. After all, this is one reason for doing mock exams.

BUT…. to do this at the expense of encouraging creativity and developing the skills of problem solving (any problem, not just particular ones), to hold back from letting students explore and evaluate?

This is partially why the new GCSE starting in September for Y10 students will be such a change for many students (and teachers). In a blog post I wrote for the Collins Maths Festival in March I said that a key feature of the new syllabus is that the Assessment Objectives (especially AO2) have changed. The linear structure of the course turns out to be, in fact, essentially spiral – requiring the revisiting of topics, gradually building on them. Students are going to be presented with questions that are more demanding and challenging. Questions are going to be set with less directed structure, making them more open ended, and problem solving will require students to use different strands of maths for solutions. Instead of the question asking students to do part a), then do b) and use the answers from a) and b) in c), students will need to find their own way through the question. Clearly, students will need to have grasped the fundamentals of maths in order to lead on to a higher level of maths achievement.

And so as far as Hannah and her sweets are concerned the problem was not that the question was unfairly difficult, it was because many students seem not to have been encouraged to explore and develop a line of reasoning. Students need to be encouraged to collaborate, discuss and explore in order to develop a better understanding of the connection of a variety of strands. It is essential that students, especially at the Higher Tier, develop reasoning, improve their ability to make inferences and deductions, and feel confident enough to challenge the validity of an argument.

Oh, yeah…… before Hannah felt hungry, there were 10 sweets in the bag, 6 orange and 4 yellow.

May 9, 2015 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

Just taken delivery of my newly co-authored Teacher Pack for the Higher Tier which was published on the 30 April. Looks great. I’m really proud of this resource. Look at my books page, and get your order in at Amazon. Thanks.

Just taken delivery of my newly co-authored Teacher Pack for the Higher Tier which was published on the 30 April. Looks great. I’m really proud of this resource. Look at my books page, and get your order in at Amazon. Thanks.

May 6, 2015 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

This thought provoking blog says something about the way that we tend to view the schooling that some of our overseas students grow up with. The school I work at has its entire intake from overseas, and is 100% boarding. Our two major client bases are Russia (and surrounding -istans) and China.

This thought provoking blog says something about the way that we tend to view the schooling that some of our overseas students grow up with. The school I work at has its entire intake from overseas, and is 100% boarding. Our two major client bases are Russia (and surrounding -istans) and China.

Chinese students are great with algebra and will solve problems until sleep overtakes them: everything must be expressed as an equation; elegant solutions are essential. Working with graph space is another matter, however, and anything that involves drawing is a struggle. Russian students also have their strengths and blind spots: they love discriminants. I realise that these are generalisations but I see this year after year as new cohorts of students arrive.

Rote learning has been a part of the lives of these students for many years, solving particular problems, getting used to specific formats. What is often lacking is the ability to identify or devise a method of solution. The questioning, evaluative skills that we value need to be developed, often with great resistance. Their background is one of passive learning where asking questions beyond clarification is not expected. The silence in the classroom is a result this ‘soaking’ up of the teacher’s mastery and the stifling of the inquisitiveness of the student’s mind – taking away the mystery of discovery, the adventure of independent learning.

I was reading an article in the ‘Time’ magazine a week of so ago about the nature of the Chinese system and the route to top American universities. In itself this was an excellent article but what really sent my own imagination running was the accompanying photograph which showed hundreds upon hundreds of students sat at exam desks in a huge outdoor playground. Row upon row; repetition; rote learning.

At this exam time I tell my students that they should not practise until they can do something right, they should practise until they will not get it wrong. Am I guilty of the things I am highlighting as a failure in other systems? Not if I have prepared the way correctly in the lead up to this period, not if I have sparked or reignited that enquiring mind.

Other systems do have fantastic elements and I am very often grateful for the work ethic that I find in students. I do not want, however, to return to the days where I would have been known as the ‘Maths Master’.

May 1, 2015 / cpstobart / 0 Comments

Started a conversation with Julia at Revision Buddies about planning the revision of the cool maths GCSE revision app that I had provided content for. If you have followed the blogs here and the ones I wrote for the Collins Online Maths Festival last month you will have an appreciation of the changes that are coming.

Started a conversation with Julia at Revision Buddies about planning the revision of the cool maths GCSE revision app that I had provided content for. If you have followed the blogs here and the ones I wrote for the Collins Online Maths Festival last month you will have an appreciation of the changes that are coming.

Watch this space!